Joanne Pohl speaks to life coach Lucy Addison about her blended style of coaching, how she left a high-flying career in finance to pursue her passion, and finding meaning in what she does.

© Joanne Pohl

“This can’t be all there is to life”

That was the thought that had confronted Lucy Addison as she contemplated her outwardly-perfect life, and considered making some major changes.

“I had had a good education, loving, generous parents, a car, a house, a partner, and a successful career. And yet, I was miserable and struggling”.

Now a life coach, Lucy helps her clients attain the goals they want to reach in their lives. The former unhappiness she experienced seems to have melted away.

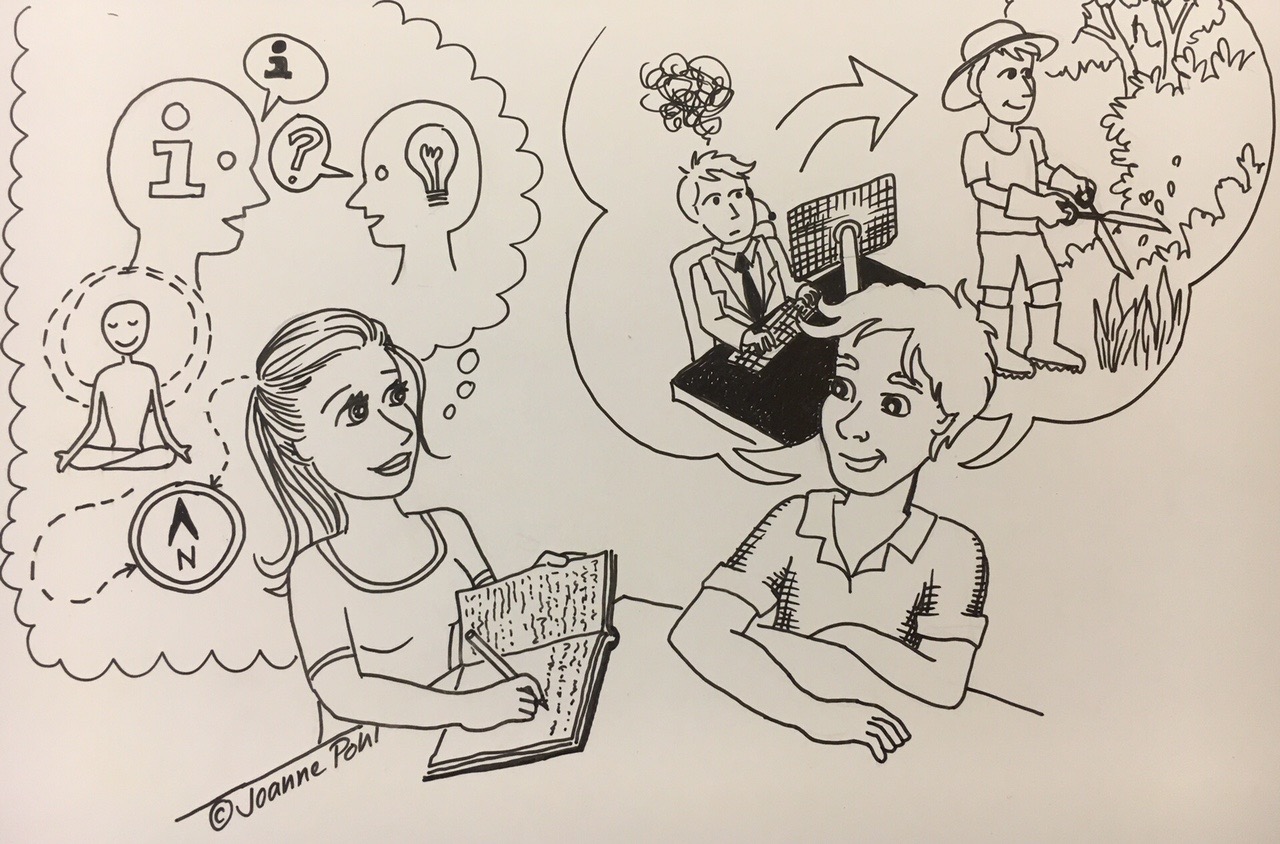

A life coach is not a psychotherapist, psychiatrist or a medical doctor, but someone who helps clients work towards reaching their goals. According to the international Association for Coaching, life coaching is a process in which the coach “facilitates the enhancement of work performance, life experience, self-directed learning and personal growth of the coachee”. The methods employed are “collaborative, solution-focused, results-orientated and systematic”.

Lucy’s definition of a life coach is a lot more holistic than the classic definitions put forward by official life coaching bodies, and she is aware of the sensitivity surrounding definitions. She describes herself as a life coach and consultant, with the latter title giving her a more liberal space within which to operate.

She sits across from me in her living room, as she tells me animatedly how she got to this point after a career in a totally different field, and how she developed her own unique style of life coaching and consultancy.

Born in Hong Kong to British parents, she attended boarding school and university in the UK, and later worked in China and the UAE. Lucy was 6 years old when her mother became terminally ill with cancer: apart from chemotherapy and other western treatments, her mother also used Chinese medicine, acupuncture, reflexology, aromatherapy, meditation, prayer, nutrition, massage and a feng shui master.

“That was the world I grew up in: one of many elements, blended,” she says.

This international upbringing, with parents who embraced the cultures they lived alongside, and living as an outsider in different cultures, has helped in her coaching work, making her sensitive to difference.

“I’m not a perfect human being, but I try to be as aware as possible, that there is more than one way of doing things.”

An alumnus of Leeds University, where she studied History and Theology with Religious Studies, she was raised as a Christian, but later eschewed that religion to a large extent and adopted an holistic approach to spirituality.

For Lucy, spirituality does not necessarily go hand-in-hand with religion or religious bodies.

“In coaching, there is a seeking involved; the client is seeking to bring about change, and that is essentially spiritual,” she explains.

Her role is a blend of personal development coach, spiritual journey-facilitator, energy healer, Emotional Freedom Therapy (EFT) practitioner and angelic reiki master.

Her approach is not one-size-fits-all in nature, and says she is able to do more classic, “pure” coaching, without the spiritual elements, dependent on her clients’ preferences.

“But if a client wants more, and wants to get more benefit from the coaching, I find the sense of being part of something bigger than just ourselves, and that we matter to the bigger picture, helps,” she says.

Apart from the traditional life coaching methodologies, Lucy also uses prayer and meditation – usually more associated with organised religion, but which to Lucy are more generalised spiritual tools – to aid the process, if the client is amenable to these processes.

“I’d suggest that when seeking is paired with prayer and meditation, there’s a faster change for the better. I think this is because there is a sense of security and groundedness that these things bring,” she says.

Aside from training in Personal Performance Coaching through the Coaching Academy, Lucy is also trained in Angelic Reiki, is an Angelic certified practitioner, and also teaches Mindfulness. Currently she is training in hypnotherapy. This gamut of experience is a big advantage, as increasingly, her clients want an holistic approach to what ails them. Lucy views the being as an ecosystem, not broken into discrete parts, and this holisticism is therefore very important to her.

“There is a grief tangible in people, that seems to make itself known when we’re not taken as the 3-dimensional beings we are. It causes stress when not all of us is taken into account by our lives and jobs.”

Lucy has first-hand experience of a corporate world that seemed to disregard the human beings that were its constituent parts, in pursuit of profits.

After graduating from university she joined a major international bank’s graduate recruitment scheme, in their corporate affairs department. Rotations within the company saw her operate at group level in London, at country level while based in China, and at both a country and regional level in the UAE. Being amongst other cultures was a highlight for her, but over time she found that the life she had pursued did not suit her. She had low energy, was ill fairly often, and saw people around her struggling too.

“I found myself wondering whether this was all there was to my life, and life in general. According to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, I had everything I could ever need, and yet I was still miserable, and I and the people around me were struggling,” she explains.

When the 2008 financial crisis hit the Middle East, where she was based, she witnessed a lot of fear, insecurities, troubles, and very little meaning to show for it.

“I found myself wondering where the humanity was. We are not machines. Human beings feel, they are creative, inquisitive, valuable and precious. Life is precious.”

© Joanne Pohl

Instead, she observed a lot more behaviour of treating humans like machines at that time. “People – men and women – disowned parts of themselves and their personalities in order to fit into the system, and I found this painful and disturbing,” she says.

“I refused to believe that this is all there is to life – that we are conditioned to set our sights on a career or role, accepted by society as valuable,” she says, firmness in her voice. She found that she needed to pursue a life that rang true to her values, and that is what she did.

Her journey from banking to her current career wasn’t a smooth transition, and took some exploration as she carved out a niche for herself.

“I wasn’t even aware of that I could have this kind of career, because what I’m doing now is quite unique in my world,” she says.

“I think a lot of people don’t understand what life coaching, or coaching in general is, but it’s getting better,” Lucy tells me. When she tells people she is a coach, they often assume of the sports variety.

“Society is very familiar with sports coaching, but life and personal development coaching is seen as a bit of a lofty term, and something that verges on the ‘woowoo’, and often veered away from,” she says.

Interestingly, she says, the corporate world have started adopting coaching more, to their benefit, but using it in a purely corporate context, for example to help management get the best out of a team.

One of the biggest benefits of her new career direction is the abundance of meaning in what she does. “As a coach, the meaning you help create, and the meaning that I have, is more long-lasting. In the corporate world, I could attach my own meaning to a project I’m working on, but it could get canned, and for very sound business reasons too. But it hurts, to lose that project, when you’ve invested so much in it, especially without being taken along in the decision making process to can it. When this occurs regularly it is challenging to create motivation and meaning in your objectives. Trust evaporates.”

I ask her whether – despite the uniqueness in each human being – there are any recurring themes or common problems that her clients face. She nods and says that almost everyone she encounters is hard on themselves, and everyone is seeking validation that they’re OK.

“We are often far harder on ourselves than we perceive the outside world to be viewing us. We make up a lot of stories about what others think about us and that often leads to us losing out on the fullness of ourselves and opportunities that come our way,” she says, adding that there’s a lot of room to be kinder, more gentle on ourselves.

I ask her what her goals for the future are, and she smiles as she tells me that in the short term, she’s looking forward to going sailing again. Her husband is a keen sailor and she’s in the process of learning. “Sailing has the potential to put you in touch with something bigger than yourself, and you feel really small out there!”

Longer term, Lucy aims to do what she can to make a bigger difference in the world.

“I want to join in, in making the world a better place, and do so by getting better at what I do. I would love to see humanity backing things where we get to be whole in whatever we are doing, and are not required to disown parts of ourselves.”

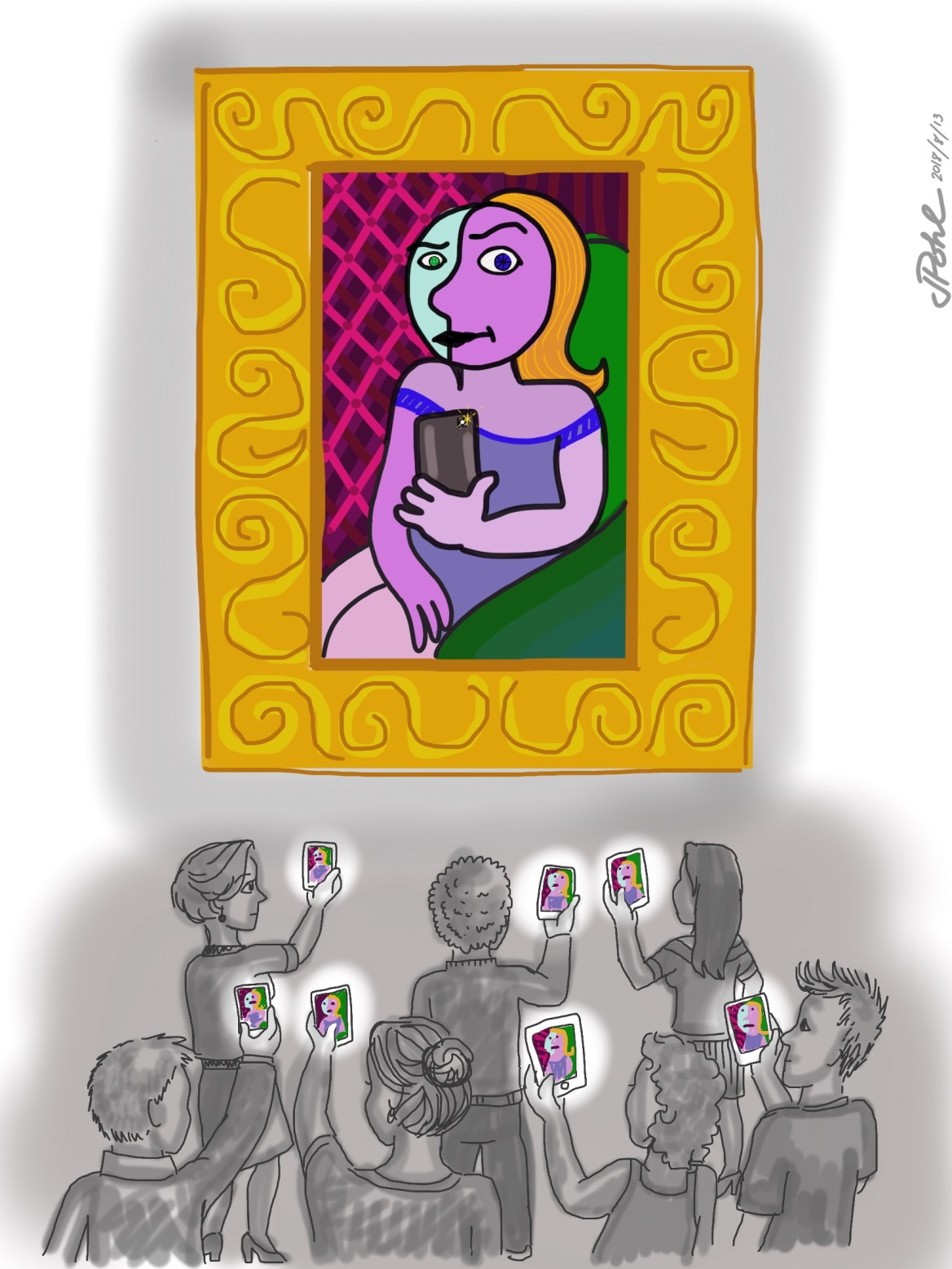

The richness and variety hasn’t waned over the years, but what I have seen is the rise and rise of people experiencing these joys through their mobile phones: recording live events and photographing artwork.

The richness and variety hasn’t waned over the years, but what I have seen is the rise and rise of people experiencing these joys through their mobile phones: recording live events and photographing artwork.